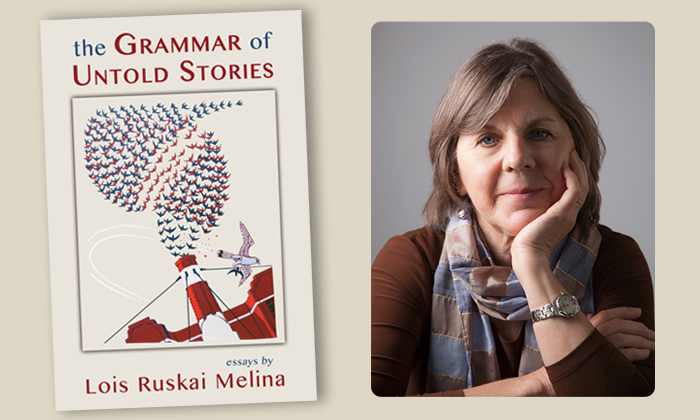

Lois Melina has been a voice of wisdom and authority in the world of adoption for decades, through Raising Adopted Children and other books, and her Adopted Child newsletter, which later became a column in Adoptive Families magazine. Her latest book, The Grammar of Untold Stories, is a collection of personal essays. We connected with Melina to discuss immigration and international adoption, transracial adoption and the Black Lives Matter movement, and the many ways adoption and infertility continue to surface in her writing.

Adoptive Families: You spent some 20 years writing about adoption in your Adopted Child newsletter and Adoptive Families magazine column, and in your books: Raising Adopted Children, Making Sense of Adoption, and The Open Adoption Experience. Your latest book contains 16 personal essays organized around the themes of Family, Work, and Home. How does adoption show up in these reflections?

Lois Melina: I stopped writing the Adopted Child column about 18 years ago. My children were grown, and I was ready for another career. I’ve been retired from teaching in higher education since 2015, and during that time I’ve focused on writing literary nonfiction and fiction.

For my collection, The Grammar of Untold Stories (Shanti Arts, 2020), I didn’t write directly about my children or being a mother. But in the essays on family and home, infertility and adoption showed up on the periphery. I think for personal essays to be of interest to people besides the author’s family and friends, they have to be able to connect the author’s experiences to larger issues. In these essays, those larger issues included heritage, ethnicity, connection, and missing pieces in family stories. Maybe I was drawn to those themes because of my experience in a family formed by adoption or maybe those are universals we all experience, and adoption is another lens on them.

One essay, “Genus, Species, Family, Order,” starts by exploring how my approach to vegetable and flower gardening differed from my husband’s interest in pasture grass and trees, but reflected more broadly on the ways we are each connected to the land itself. I wanted to acknowledge in that essay that my experience with that is likely different from that of my children, who were born in one country and brought up in another, but I stopped short of speculating on their feelings because that’s not my place.

In the final essay, I wanted to explore what home means to me as someone who’s lived in different places. I discuss how animals like salmon and dragonflies and birds find their way back to where they were born. As I wrote about what happens to animals when homing mechanisms are disrupted—by fences, for example—I thought about the ways adoption has disrupted the ability of some children to find their way “home.” The adoption piece is not the focus of the essay, because I’m writing about me and not my son or daughter, but that awareness hovers on the edges.

AF: The title essay tells about a trip you made to the village in Hungary where your paternal grandmother was born. Your son and daughter were born in Korea. Did you gain any new insights into the experience of immigration through your visit or by writing this essay?

LM: I never had a strong drive to explore my genealogy. Maybe my attitude explains why I was open to adoption years ago, or maybe I didn’t want to give a lot of attention to something that could be difficult for my children. At any rate, the trip to my grandmother’s village wasn’t a culmination of years of research on Ancestry.com, but just a side trip when my husband and I were visiting Hungary—something interesting to take us “off the beaten path.” I found myself surprisingly and profoundly moved by coming into contact with this place where my grandmother was born, hearing the language that I hadn’t heard since my grandmother died 58 years ago, and learning a story that had never been talked about in our family. I found myself reflecting on what it meant for her to leave that village and come to a place where she didn’t speak the language, how her language was part of her identity, how language connected her to her origins.

Right after we left Hungary, there was a surge of immigration from the Middle East that the Hungarian authorities were trying to stem. So on the one hand, I was imagining my grandmother setting off for this new country because staying in her village had its own risks, and on the other, seeing how people like my grandmother were being treated just because they were trying to leave an untenable situation and be reunited with their families.

Although my children’s experience is not part of the essay, I certainly thought about them as I wrote it. I realized that I thought of and described my children as “international adoptees” rather than “immigrants.” So writing that essay in some ways reframed international adoption for me. As I read about policies pertaining to children brought to the United States from Central America because their parents wanted a better life for them, children who have only known life in the United States but whose residency status is tenuous, I realized there are more similarities than differences between them and international adoptees.

AF: How do you think you might have written differently about immigration, genealogy, “home,” and even infertility if you’d set out to write a memoir rather than individual essays?

LM: My experience is that I always learn something when I write. Even when I think I know the story I’m going to tell, I often find something shifting in me. When I started to write The Open Adoption Experience with Sharon Kaplan Roszia in the early 1990s, open adoption was gaining traction. I wasn’t completely sold on it, but I believed people who were embarking on it needed guidance and support. By the time we finished the book, I was no longer ambivalent but a strong believer that open adoption was another kind of family relationship, one that might take a lot of work, but that deserved that extra measure of work and grace.

So, I think I would have learned something and connected to important questions and arrived at some measure of truth if I’d set out to write memoir, but they might have been different questions and different insights. Hopefully just as honest. What essays allowed me to do is vary the point of view, which allows for seeing a subject from different perspectives. I wasn’t trying to construct a narrative about my life as much as explore different facets. In the end, I think I created a solid if incomplete look at my adult life.

AF: In “The Four Seasons of Longing” you imagine four girls you didn’t give birth to as a result of infertility. How did this essay come about, and did it surprise you to write about infertility so many years after you adopted?

LM: That essay began with a writing prompt about Autumn in a Corporeal Writing workshop with Lidia Yuknavitch. We all wrote in our journals for 15 minutes. I had no intention of writing about infertility. I hadn’t ever imagined these girls before, but the emotional safety that Lidia builds in her workshops allowed something deep inside me to surface. It surprised me that this was there after all these years. Now comes the moment where, as an adoptive parent, I feel compelled to say that, just because I could tap into the fantasy children I didn’t give birth to, it doesn’t mean I’m carrying regret. One of the messages I tried to convey when I wrote about adoption is that adoptive parents and adoptees can have conflicting emotions, conflicting longings. We can grieve for the children we don’t have and those losses don’t have to diminish or hinder our love for the children we do.

The point of the essay is that we all have longings. We carry them deeply. Some of them aren’t realized. Some of them don’t go away even though we go on to have loving and satisfying lives. My hope is that this awareness leads to greater empathy and compassion.

AF: It’s been almost 40 years since you first wrote about adoption as a way to help adoptive parents understand how infertility and adoption impacted them and their children. How do you think our understanding of adoption has changed in that period of time? Where do you see we as a society and as an adoption community still have work to do?

LM: I haven’t been as involved in adoption education or activism since I stopped writing for Adoptive Families, so I’m in many ways on the outside looking in. I’ve seen some progress in laws opening records and allowing people to decide for themselves what a “family” can look like. DNA testing has facilitated those seeking to meet or reunite with family members separated by adoption. But this progress has been unnecessarily slow and arduous and is still tenuous in many ways.

What is troubling, though, is that when I see stories on social media, in the news, in memoir, it seems that the emotional challenges of adoption remain as difficult as ever. Adoption is a profound loss, so some amount of suffering is always going to be part of the experience. But some of the pain could be mitigated with better education, better use of existing resources. There are still adoptive parents who are uninformed about the histories of children who are older at the time of adoption, adults whose birth families do not want to reunite, adoptees who grow up with hurt and grief and confusion that isn’t understood or supported by their adoptive parents. I started writing Adopted Child in 1981 because there almost no resources available to address those challenges. Social workers didn’t have adequate training. Therapists didn’t have adequate training. But there are a lot of resources now, and I wish more people would know about them and would take advantage of them.

I also want to note that over the last 40 years, our institutions have put far more resources into creating solutions for infertile or single individuals who want to become parents than we have into creating solutions for mothers—and fathers—who feel so challenged by their lives that parenting is or feels overwhelming. We’ve allowed biases to influence policy. We have to do better.

AF: You live in Portland, where there have been continuous protests by Black Lives Matter activists since the death of George Floyd. You are the white mother of a son and daughter from Korea. How do you think the BLM movement contributes to the ongoing debate around transracial adoption?

LM: In the late 1980s or early 1990s, Jim Mahoney, a therapist from Spokane, Washington, gave a workshop for white parents who had adopted transracially. He told us that if we raised children of color with the kind of privilege we enjoy—simple things like how we talk to the police if we’re stopped, or how we might knock on someone’s door to ask to use the telephone in an emergency—we could get our children killed. He was describing having “the talk” with them. It was eye-opening for me. And I think the Black Lives Matter movement has helped all of us recognize the daily dangers that Black people of all ages live with. I think it has moved many white parents to dig deeper into their own attitudes and behaviors and to take on more advocacy on behalf of their children. And I want to acknowledge that much of that introspection and advocacy has been messy and awkward and painfully slow and that not enough white people have even taken up that work.

What we’ve also seen lately is both an uptick in racial violence directed at Asian Americans and more awareness of how Asian Americans have experienced racism. Because Asians have been stereotyped as the “model minority,” white parents who adopted children from Korea and China have probably been even less prepared than those adopting Black children for the racism their children would encounter.

I know that organizations and businesses are finally going beyond the superficial “diversity training” of the past. Because I’m no longer involved with adoption organizations, I don’t know if today’s prospective transracial adoptive parents are being asked to probe their own privilege and racism in deeper ways, but I hope so.

And I hope that as we grow in awareness, we revisit some of the assumptions about race and class that have been used to justify removing children from their biological families and placing them with white parents. Maybe we need to change policies and practices, maybe not. But we can’t even have those discussions unless we are honest about the racial and class components of those practices.

AF: How can people find your essay collection, The Grammar of Untold Stories?

LM: The book can be ordered through any independent bookstore, as well as from Amazon. More information, links to readings, and links to my short stories can be found at loisruskaimelina.com